|

| (VOA News) |

On March 3, at a speech to Republican donors in Florida, Donald Trump offered these comments on Xi Jinping’s accession to lifelong presidency:

“Don’t forget China’s great. And Xi is a great gentleman. He’s now president for life. President for life. No, he’s great. And look: he was able to do that. I think it’s great. Maybe we’ll have to give that a shot someday.”

Imagine that Eisenhower had praised Mao in these terms.

Yes, George Washington is spinning in his grave, and yes, Trump

is a fake American. From “lock her up” to president-for-life, Trump has daily attacked

the liberal democratic values of the rule of law, the separation of powers, and

the peaceful transfer of power. But why should Trump endorse dictatorship

abroad?

Trump’s rejection of liberal democracy domestically

corresponds to a rejection of liberal institutionalism in the realm of foreign

policy. Just as we are America First, he says, so, too, should you all be

Yourselves First. We will see to “our own”; you see to yours. We will protect

ourselves militarily and economically; you do the same. We owe each other

nothing. And to you oppressed people, wherever you are, we say—nothing. You’re

on your own. You’re invisible. It is a foreign policy very much in line with

the professed non-interventionist ideals of the Chinese Communist Party: the

rights of states trump the rights of peoples and individuals.

In short, Trump’s foreign policy is a form of realism: the

belief that states should look after their own security and nothing more. You

might agree. You might think that groveling before the leader of the world’s

other superpower is conducive to our security. Perhaps not, but you might ask

whether or why America should have any interest in the accession of a new

emperor to China’s throne. In answer, I here present two cases in which, in its

relations with China, America did not adhere to its own values, and opted

instead for mere realism, with disastrous results for both nations.

America supports the last would-be emperor

Word of the planned constitutional changes legalizing Xi’s

life tenure was greeted with dismay by many of China’s citizens. As usual, few people

publicly and directly stated their thoughts (though a brave few did), but in

the wave of oblique, code-worded, and fast-deleted online protests, one

particular comparison stuck out: Yuan Shikai, a warlord who is remembered for

trying to roll back China’s republican revolution by seizing the presidency and

declaring himself emperor.

|

| Yuan Shikai being pompous (Public Domain) |

In late 1911,* the Qing dynasty was wracked by series of military uprisings, mostly in South China, known as the Xinhai Revolution. On December 29, 1911, a provisional national assembly elected Sun Yat-sen first president of the Republic of China, which was declared on January 1, 1912. Lacking the military power to oust the remnants of the Qing dynasty in North China, Sun soon felt compelled to make a deal with Yuan Shikai, whose Beiyang Army, based in the North, was then the most powerful fighting force in the country. In exchange for the presidency, Yuan would force the last Qing emperor, Puyi, to abdicate. Sun thus stepped down after two months as president, and Yuan became the second president of the republic.

China’s first parliamentary election was held in 1912-1913,

and Sun’s Nationalist Party won a majority. I feel that this election

represented a genuinely hopeful moment in Chinese history. Despite no prior

history of democracy or any sort of legal tradition similar to those which

underpinned the development of democracy in the West, a parliament was

democratically elected by a broad electorate. The parliament was set to elect

Song Jiaoren, a leader of the Nationalist Party and a scholar of the American

constitution, as prime minister. Song campaigned on a platform of the

separation of powers and checks on the presidency in particular. This sat not

well with Yuan Shikai. En route to Beijing on March 20, 1913, Song was shot and

killed in Shanghai Railway Station. The evidence pointed to a hit carried out

by the Shanghai mob at the instigation of Yuan, but the investigation into the

murder was cut short by the assassinations of those involved.

|

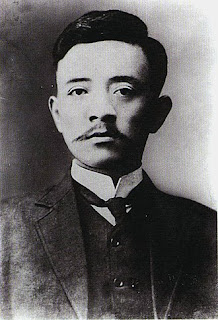

| Song Jiaoren (Public Domain) |

Yuan, demonstrating some real savviness, responded to Song’s slaying by asking America to pray for his nation. The Americans ate it up: soon after, the US government become the first to declare its official recognition of the Republic of China, and a few months later, State Department officials in China suggested to Yuan that he seek American legal advice on crafting a constitution. The man chosen was Columbia professor Frank Johnson Goodnow, who turned out to be no friend to liberal democracy. In arguments which would later be echoed in later generations by intellectuals supporting Chiang Kai-Shek’s dictatorship and then that of the Communist Party, Goodnow claimed that the Chinese people, having no experience with law or self-government, were unprepared for democracy. He wrote the republic a constitution with few freedoms guaranteed for the people and a very strong executive branch whose powers included the ability to appoint the legislature.

In what was later called the Second Revolution, military

uprisings against Yuan followed, and he took the opportunity to outlaw the Nationalist

Party and pack parliament with allies. This parliament approved Goodnow’s

constitution, and various American diplomatic and legal voices supported the

move. When Yuan decided to declare himself emperor in 1915, Goodnow wrote him a

memorandum approving of the restoration of the monarchy, reiterating his

position that the Chinese national character was suited for nothing but

despotism. Domestically, Yuan faced continual political and military resistance

to his imperial ambition, and in 1916, he abandoned his claim to the throne

before he could ceremonially accede to it. He died of illness shortly thereafter.

We cannot know that the republic would have been successful

without American meddling, but consider: it was democratically elected Chinese

political leaders who themselves opted for an American-style constitution, and

it was American diplomatic attachés who declared that China must return

to its autocratic traditions. What if America had supported the aspirations of

China’s liberals and democrats instead of its would-be emperor? Would a robust

system of liberal republicanism or liberal democracy have developed? Could the

subsequent decades of warlordism, Chiang Kai-shek’s fascism, Japanese

occupation, and Mao’s totalitarianism have been avoided? What we do know is

that the national government was delegitimized in its infancy, a series of

hapless presidents followed, the country fragmented into warlordism, and in the

absence of central authority, Japan invaded.

Woodrow Wilson fails China

China was one of the Allies in World War One. Its

contribution to the war effort was to send about 140,000 laborers, mostly

impoverished men from Shandong Province, to the Western Front, where they

worked in support positions for the British and French armies, building the

infrastructure of war: trenches, railroads, airstrips, etc. Their labor,

intended to free up British and French men for front-line service, was

ill-compensated and to some extent resented by the Allied soldiers, but it made

a substantial contribution to the war effort.

Japan also joined the Allies. The empire’s focus was on

expanding its sphere of influence in Asia, specifically China, and gaining

recognition as a Great Power. Early in the war, Japan occupied the territories

which Germany had seized in Shandong Province in 1897, specifically the area

around Qingdao, known as Jiaozhou.

As the war drew to an end,** Woodrow Wilson hoped that the concluding negotiations could cement liberal, idealist

principals into international law. On January 8, 1918, he delivered a speech

summarizing his Fourteen Points, primary among which were open agreements

between states, anti-militarism, self-determination, free trade, and “a general

association of nations”—what would become the League of Nations. The first

point, a repudiation of secret negotiations, may strike readers today as

hopelessly idealistic, but it was received with great acclamation worldwide at

that time, particularly in China, which had long been the victim of imperialist

collusion among the Great Powers and self-interested Chinese leaders. Indeed,

the Fourteen Points were taken to heart by

colonized and brutalized peoples across the globe, and expectations for the

outcome of the Paris Peace Conference ran high. Many thought that with the

guidance of Wilson’s vision, the War to End All Wars would do just that.

At the Paris Peace Conference, the Chinese negotiators

initially hoped that, in keeping with Wilson’s stated principles of political

and economic self-determination, all of the unequal treaties which the Great

Powers had foisted upon China in recent decades would be overturned. When it

became clear that this was impossible, they felt confident that they could at

least secure the return of the Jiaozhou concession to China. Historically,

geographically, and even spiritually (as it contained the hometown of

Confucius), the Jiaozhou concession was rightfully Chinese.

Wilson, though giving no specific assurances, had made it

clear to China’s minister to the United States, Wellington Koo, that China

would have America’s support in the negotiations. In the end, however, the

Japanese negotiators convinced the Americans as well as the representatives of

the other Great Powers to support their claims on the basis of a secret exchange

of missives which had occurred between the Chinese and Japanese governments—unbeknownst

to China’s negotiators—just a few months before the conference. In these

letters, the Chinese government specifically conceded to Japan’s demand for the

Jiaozhou concession. Thus, as there had already been a bilateral agreement, the

Japanese argued, the law was on their side. Koo argued that Japan’s position

was premised on the old order of predatory, imperialistic diplomacy, and that

in the age of the Fourteen Points, such secret agreements should hold no

weight. It turned out, however, that both Britain and France had secretly

promised to back Japan’s claim to Jiaozhou. Wilson finally instructed his

negotiators to tell the Chinese to accept the transfer of the concession to

Japan in exchange for a verbal promise from the Japanese that it would be

returned at a later date. The Chinese countered that this should be in writing,

but the Japanese—with truly remarkable cynicism—said that they would not brook

the implicit assault on their integrity. Wilson, concerned with pleasing the

European Allies and ensuring Japan’s participation in the League of Nations,

ultimately overrode the objections of Edward T. Williams, the American

delegation’s Sinologist, and the final text of the Treaty of Versailles,

unsigned by China, recognized Japan’s claim to Jiaozhou.

The Paris negotiations were thus marked by precisely the

sort of secret agreements which Wilson had repudiated in the first of the

Fourteen Points, and anger with Wilson’s and America’s hypocrisy spread like

wildfire through China, where news of the Paris conference’s results triggered

a political earthquake: on May 4, 1919, about three thousand students protested

in front of the Gate of Heavenly Peace in Beijing, condemning their own

government for collaborationism and the Great Powers for their greed and power

politics. The movement spread throughout China and ultimately led to the transformation of the entire character of Chinese thought in the New Culture Movement.

|

| Students protesting the Treaty of Versailles (Public Domain) |

One of the ideologies which took root in China in this area of disillusionment and soul searching precipitated by the Paris Peace Conference was Bolshevism. A young Mao Zedong took part in the May Fourth Movement, publishing a temporary magazine in which he condemned the cynicism of the Great Powers and suggested that Bolshevism, which he believed (wrongly) to be deeply involved in the anticolonial struggles in India and Korea, might present a worthwhile alternative to liberalism—an ideology in which he had previously shown interest. Mao was not alone. An entire generation of youth whose faith in liberalism was shattered by the Paris Peace Conference began to ponder Bolshevism as a better path toward national self-strengthening and resistance to imperialism. Wilson’s failure to uphold his own principles drove them into Lenin’s arms.

In allowing the transferal of Jiaozhou to Japan, America not

only failed to live up to its ideals, but also failed to act in its own

interests. Tensions between Japan and America had already been rising for years

because of Japan’s relentless expansionism, and Sino-American relations had

been strengthening. If Wilson had not allowed Japan to cynically manipulate the

letter of international law, the empire might not have been so bold as to

continue expanding in China. How much might this have reduced the likelihood of

the Pacific War and the Second Sino-Japanese War? Furthermore, a young

generation of Chinese, including Mao, might have stuck with liberalism rather

than turning to Bolshevism, with all the disastrous results that followed.

A fake president applauds a coronation

Returning to Trump’s accolades for the new emperor on the

occasion of his mounting the Dragon Throne: what, you may ask, would I advocate

that Trump do instead?

The problem is not that Trump neglected to criticize a

violation of what America previously contended to be universal human values.

The problem is that he is praised it. It isn’t just a moral abdication; it is a

strategic abdication. To endorse dictatorship in exchange for nothing at all

represents a concession in exchange for nothing. At present, the language of

values is still a form of leverage which America could wield if we had a

president who had any values, but Trump doesn’t understand what America is or

how diplomacy works.

The two historical examples above show that America doesn’t

do realist foreign policy well. Liberal institutionalism has been

America’s method of subduing the world, of drawing it into a peaceful and

prosperous order which benefits America. And in both of these cases, abandoning liberal principles in China policy led to catastrophe.

China is not a nihilistic dictatorship in the vein of

Putin’s Russia. Whether or not you believe that the leadership of the CCP

personally cares about morality, they have always sought popular moral

legitimacy. They have always sought to mold the character of the people in

their own image. They have never ceased being dedicated to “thought work.” It

isn’t enough that people fear them and tolerate their rule; they want people’s

hearts. This has been a preoccupation of all lasting Chinese regimes since the

Han dynasty. It hearkens back to Confucius: “One who rules through the power of

Virtue might be compared to the Pole Star, which simply remains in place while

receiving the homage of myriad lesser

The CCP regards liberalism as a poisonous contagion, an

infection which corrupts the hearts of people both simple and clever, and they are

terrified of the appeal which liberalism holds for Chinese people. Ironically,

they ignore the Western origins of their professed socialism and label

liberalism as something inherently foreign to Chinese culture and therefore

unfit for transplantation into Chinese soil.

A major source of cognitive dissonance and frustration here is of course the success of liberal Taiwan and its reluctance to reunify with China. The CCP doesn’t just want to be loved by the Chinese people, but to accepted by the Taiwanese people. But China has something Taiwan does not: international prestige. They want not just to be accepted by Taiwan, but to be admired by the world. If they can’t have Taiwan’s admiration, they can perhaps buy some elsewhere, and the more admiration the win elsewhere, the more likely (they think) Taiwan will be to come around.

A major source of cognitive dissonance and frustration here is of course the success of liberal Taiwan and its reluctance to reunify with China. The CCP doesn’t just want to be loved by the Chinese people, but to accepted by the Taiwanese people. But China has something Taiwan does not: international prestige. They want not just to be accepted by Taiwan, but to be admired by the world. If they can’t have Taiwan’s admiration, they can perhaps buy some elsewhere, and the more admiration the win elsewhere, the more likely (they think) Taiwan will be to come around.

Even putting the Taiwan issue aside, the CCP desires the international

moral prestige which used to flow to China through the tributary system, and so

do the Chinese people. Both the Party and the people feel that this only befits

China given its glorious history. The value of this international recognition

in the formula of national rejuvenation should not be overlooked.

The CCP’s desire for moral legitimacy gives their would-be tributaries leverage over them. It is entirely up to the international community whether or not to to give it to them. It particularly rests in the hands of America, which—for better or for worse and for a while yet, at least—remains the incumbent Pole Star. Wielding this leverage is as simple as making public statements. It is as simple as stating that dictatorship is a violation of human dignity. But such a statement could only be made by a leader who had a conception of dignity. By a president who didn't want to be a dictator.

*This section draws heavily on John Pomfret’s account in The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom, pp. 133-136.

**This sections summarizes Erez Manela’s account in The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins

of Anticolonial Nationalism, chapter 9.

***Ivanhoe & Van Norden. Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy, p. 4.